We don’t know exactly when humans first settled in the Japanese archipelago; Archaeologists will only confirm evidence of Paleolithic (Palaeolithic, aka. The Old Stone Age) people living in Japan from around 35,000 years ago, although there are those who think the first colonizers arrived much earlier.

Archaeologists think the Japanese islands were colonized by Paleolithic people arriving via at least two routes, one from the south and another from the north. DNA scientists now think that the paleolithic ancestors of the Jomon people came from the northeast part of the Asian mainland continent. This period was called the Paleolithic era (some archaeologists also call it the Pleistocene era). Paleolithic Japan lasted for 20,000 years until about 10,000 years ago, which is when another distinctively different culture and group of people called the Jomon began to live and spread out all over Japan. What stood out about the Paleolithic people was the numerous stone core tools they left behind. Paleolithic comes from the Greek words “paleos” which means “old” and “lithos” which means “stone”.

Who were the first settlers of Japan?

The first settlers lived by hunting and gathering, used fire, and made their homes either in inland caves and rock shelters. An 8 year old child’s bones from 32,500 years ago were found in the Yamashita Daiichi cave. The child was nicknamed “Yamashita Dojin“.

The Minatogawa Man, however, is the most famous of the Stone Age residents and is considered to be a direct ancestor of the Jomon people, and therefore one of ancestral lineages of some of the modern day Japanese population. An 18,000 year old fossilized resident of Naha city in Okinawa, he was 155 centimetres tall, had large teeth, jaws with two of his teeth knocked out – the earliest example in the world of this rather common global tribal custom. He had a high, broad and pinched nose but a low and narrow forehead with a prominent browridge.

It has been said that the Minatogawa Man resembled a number of men from the fossil halls of history, namely, the Liukiang man and Zhenpiyan man of South China, Lang-Cuom and Phobinhgia man of North Indochina. Others disagree and say he looked most like the Sinanthropus of China and Wajak man of Indonesia, or a cross between the Sinanthropus and West European Neantherthal (Hisao Baba, Banri Endo). But you might want to know this piece of trivia…the Minatogawa Man is thought to have landed in the dump where he was, with a heap of other bones, because he had been attacked by cannibals.

On the mainland of Japan the skeleton of the Hamakita man was found in a limestone quarry site in Hamakita city, Shizuoka prefecture in central Japan. Hamakita man’s fossils were radiocarbon dated back to 17,900 years ago. Like the Minatogawa man, the Hamakita man is also considered to be a probable ancestor of the Jomon people. On Honshu Island, along with the Hamakita man, another find of a human fossil, the Mikkabi man came from a quarry northwest of Hamamatsu city. The bones were judged to resemble closely the Jomon people of the Neolithic age.

Most recently (Asahi, Jun 2,2011), Late Pleistocene human remains were reported to have been discovered in the Ryukyu Islands‘ Shiraho-Saonetabaru Dōketsu (2011/02/06)

Below is a list of human fossils from Okinawa in the Japanese Palaeolithic period:

|

As can be seen from known lists of human fossil remains, they are mostly concentrated on the Ryukyu Islands in southwestern Japan, suggesting that there may have been a northward migration via the Ryukyu Islands. In contrast, studies of ancient mitochondrial DNA demonstrate genetic continuity among Holocene hunter-gatherer populations in the Paleo-Sakhalin-Hokkaido-Kurile Peninsula, however, the Pleistocene genetic history of Japan is little explored.

Thousands of sites have been excavated all over Japan showing up a variety of Paleolithic stone tools…you can see why many people call this period the Stone Age of Japan. However, only a few skeletons in good condition have been rescued from the inevitable decay in Japanese soil. That’s because the soil is very acidic and does not allow for preservation of fossil matter.

The Paleolithic people made large and rough core tools by working on a fist-sized piece of rock (called the core) with a similar rock (called the hammerstone) and knocking off several large flakes and chipping away the surface of a stone. They also produced flake tools by working with a stone flake broken off from a larger piece of stone. These stone tools are like the “signature” or “footprints” left behind by the Paleolithic people, and the various tools that were produced include trapezoids, edge-ground stone axes, backed-blades, leaf-shaped bifacial point-tools, pebble tools, grinding and pounding tools, and microblades (tools with blades smaller than 1 centimeter).

Wherever Paleolithic people made their base campsites, they left behind traces of many small flakes and chips from the manufacture and maintenance of stone tools. Even at their work camps and butchering sites, and temporary sites, they would have left lots of stone flakes and chips – the telltale signs of tool sharpening. And that’s what archaeologists look out for when they go digging in search of Stone Age finds. Only a few tools made of bone have been found.

They left behind stone tools, fire-cracked rocks or fireplaces, stone materials, and other artifacts everywhere. From examining the stone materials left behind by the Paleolithic people, experts know they traded extensively stone materials and stone tools.

From a site in southwestern Hokkaido dated to near the end of the Late Paleolithic period, scientists gathered that they buried their people and decorated their bodies.

We also know that the Paleolithic people were already skilful at crossing wide stretches of sea since obsidian was being obtained from Kozu Island south of Tokyo. They were very likely on the move a lot and did not settle down anywhere long.

Most sites were occupied for short periods of time — a few days to a few weeks or months — and then not used again for thousands of years. The Paleolithic people appear to have preferred caves over solid structures for homes, although it is thought a few of the Paleolithic people may have also started living in pit dwellings. However, in actual fact, experts believe that very few people actually lived in caves, that the Paleolithic people in Japan mostly lived in superficial portable homes made of animal skins, that have left no permanent traces for us to discover.

Did they invent pottery?

For a long time, archaeologists and historians called this period in the history of the Japanese archipelago, the pre-Ceramic era, because for the most part, pottery had not been invented yet. However, bits of pottery (called sherds) have been turning up with earlier and earlier dates, and the earliest pieces discovered are dated to 16,500 years ago, towards the end of the Paleolithic Period, though such finds have not been many. So perhaps, the Stone Age man in Japan experimented with clay and invented pottery?Why archaeologists think discovering the first potsherds in the Paleolithic era is so exciting is because it means that pottery was invented before agriculture and permanent settlements. This bucks all previous thinking that pottery was invented only when people began to farm the land and needed pots to store their food in.

What did people eat?

Scientists know that the people were mostly fishing from rivers and hunting in the forests. They also gathered fruits and nuts such as hazelnuts and berries.

The Hatsunegahara site in Shizuoka offered up 56 prehistoric pit traps that tell us how the people caught animals such as wild boars and even Naumann elephants, giant fallow deer and bison, between 27,000 and 25,000 years ago. However, the pit traps of the Otsubobata site in Tanegashima are now thought to be even older dating to 30,000 years BP.

Some food remains were identified from the Lake Nojiri site along with artifacts like a bone cleaver, bone flake tools. These suggest a killing and butchering site for Nauman’s elephants and Yabe’s elks. But experts are not certain whether people hunted and killed these animals for food or merely scavenged them. Others argue that the tools the Paleolithic people used were more suited to the hunting of smaller animals rather than larger animals.

The climate and environment during the Paleolithic era

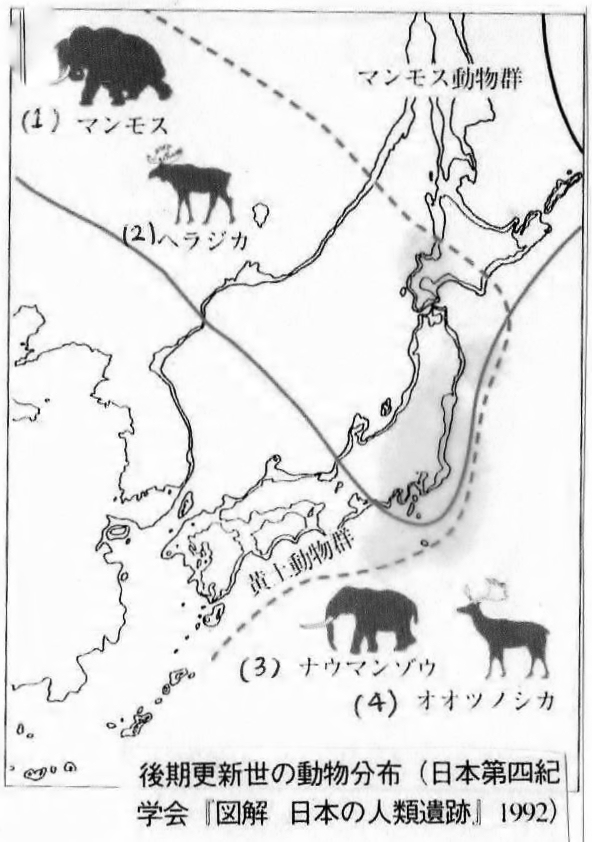

There had been 4 ice ages over the Paleolithic era, and the climate was mostly cool to cold. So that surviving the cold and the elements must have been a daily concern for the Paleolithic people. Approximately 20,000 years ago, during the Wiirm ice age, Japan was connected to the continent and sea level was 150 metres lower than it is today.

The temperature was 7-8 degrees lower than that of today and at the peak of the glacial cold around 21,000-18,000 years ago, tundra covered much of Hokkaido in the north. Most of the rest of eastern and central Japan (in the subarctic zone) was covered with boreal forests of trees like larch, spruce and Japanese hemlock. Western Japan from the Kanto Plain around Tokyo to Kyushu was covered with a temperate coniferous forest.

The Naumann elephant(Palaeoloxodon naumanni) and other large animals like Yabe’s giant deer(Sinomegaceros yabei) that are extinct today, lived in Japan and in the region during the Paleolithic era.

Many people believe that the Paleolithic hunters in Japan (and elsewhere) hunted to extinction these large mammals. Moose, brown bear, steppe bison and aurochs were among the many large animals that lived in the forests of eastern and northern Japan, along with many Arctic animals. A recent 2009 study concluded that the extinction of megafauna specifically the Palaeoloxodon, Mammuthus and Sinomegaceros was caused by the colonization by pre-Jomon groups of Japan, and to a greater extent than previously thought.

References and further readings:

Baba, Hisao, A Short History on the Findings of Paleolithic Human Remains in Japan and Significance of the Minatogawa Skeletons幻の明石原人から実在の港川人まで February 2020, TRENDS IN THE SCIENCES 25(2):2_34-2_37

Baba, Hisao, A Short History on the Findings of Paleolithic Human Remains in Japan and Significance of the Minatogawa Skeletons 幻の明石原人から実在の港川人まで, February 2020, TRENDS IN THE SCIENCES 25(2):2_34-2_37

Yuichi Nakazawa, On the Pleistocene Population History in the Japanese Archipelago, Nov 2017, Current Anthropology 58(S17):S539-S552

A model for the origins of the Japanese Palaeolithic by Charles T. Keally

Hisao BABA and Shuichiro NARASAKI (1991). Minatogawa Man, the Oldest Type of Modern Homo sapiens in East Asia (PDF). 第四紀研究(The Quaternary Research) 30 (2): 221-230. doi:10.4116/jaqua.30.221 2015年12月23日閲覧

A History of Japan (Blackwell History of the World) by Conrad Totman

A Model for the Origins of the Japanese Paleolithic by Charles T. Keally

Japanese Palaeolithic Period by Charles T. Keally

The Paleolithic age in Okinawa

Imamura, Keiji Prehistoric Japan | New perspectives on insular East Asia Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996.

Cambridge History of Japan Vol. 1 Ancient Japan Delmer M. Brown

M. Kondo, S. Matsuura, Dating of the Hamakita human remains from Japan

2005, Biology Anthropological Science

Hisashi Suzuki; Kazuro Hanthara et al. (1982). “The Minatogawa Man – The Upper Pleistocene Man from the Island of Okinawa“. Bulletin of the University Museum (University of Tokyo) 19.

Suzuki, Hisashi Skulls of the Minatogawa Man (Chap 2)

Minatogawa People (an Asian Neanderthal?) by Hisoa Baba/Banri Endo

Minatogawa Man, a review of Paleoanthropology by P. Browne

Suzuki, Hisashi Mikkabi man and the fossil-bearing deposits from Tadaki limestone quarry at Mikkabi, central Japan J-STAGE home, Journal of the Anthropological, 1962 Volume 70 Issue 1 Pages 1-20

Norton, Christopher J. et al. The nature of megafaunal extinctions during the MIS 32 transition in Japan Quaternary International (2010)

Japanese Beginnings by Mark Hudson

Sato, Hiroyuki Late Pleistocene trap-pit hunting in the Japanese Archipelago, Quaternary International, Volume 248, 18 January 2012, Pages 43–55 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.03

Hatsunegahara site | 日々のできごと、ときどき考古学: Archaeological days and so on

Permanent exhibits and dioramas at the Sagamihara History Museum and Tokyo National Museum, Yokohama History Museum, images above belong to Heritage of Japan except where otherwise attributed