The earliest Jomon developed and used pottery for fishing salmon and molluscs 15,500 years ago

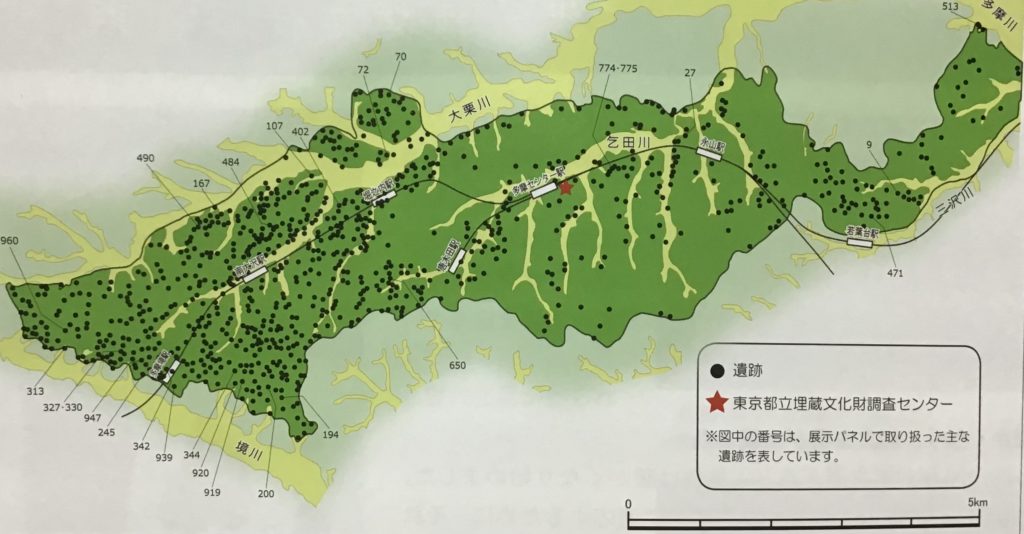

Today, I begin a series on the Jomon Village of the Tama Hills (which I have visited probably over 10 times!). Archaeologists have excavated 770 out of the 964 sites from the Tama Hills (aka the Tama New Town to locals). A “Jomon village” based on settlement traces was recreated, with archaeological exhibits from 40 years of diggings on display at the adjacent Exhibition Hall run by the Tokyo Metropolitan Archaeological Center.

People began living in this area around 32,000 years ago, towards the end of the Ice Age when the climate was colder and more like Hokkaido’s, and when people hunted game such as Giant Elk and Naumann elephants, salmon from the rivers and large animals that lived in the coniferous forests. (They left behind stone tools and burnt stones from their fires, but I will post in another episode about the Upper Palaeolithic traces and remains, because the focus of this post is the Jomon people from the Maedakochi site).

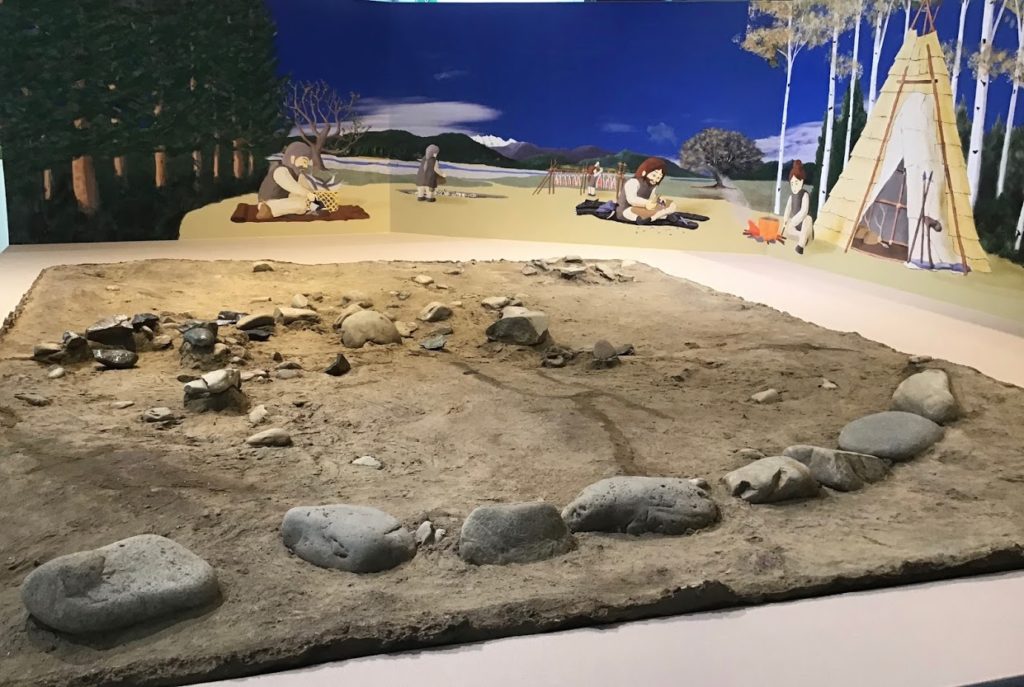

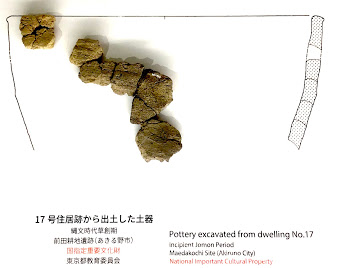

The Maedakochi site is currently the central exhibit being featured at the Exhibition Hall of the Jomon Village(scroll to the top of this page to view photo).

Significance of the Maedakochi Site, Incipient Jomon (ca. 14,000–4,000 BCE)

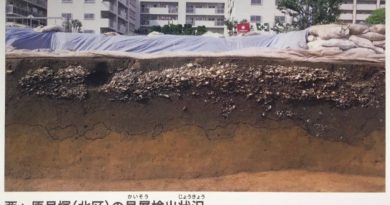

The Maedakochi site in Akiruno city, is an archaeological site that is one of the oldest Jomon sites in Japan. In addition, dwelling site no. 17 is famous for the rare find of thousands of salmon teeth remains.

The recreated scene is one at the beginning of autumn, and based on the research data on the Maedakochi site, the people who lived there are depicted as catching salmon going up the river and processing it into preserved food. They are also busy at work making hunting tools out of deer antlers, and processing bear fur. The climate was cold, the research on the landscape of the site shows there was a spruce forest and other coniferous trees around it.

Researchers have fixated on and studied the numerous remains of salmon bones found at the Maedakochi site.

“The earliest site which yielded salmon bones is the Maedakochi site (Incipient Jomon, Tokyo) in which many salmon teeth were detected in the burnt soil deposited in a pit dwelling. In other periods, salmon bones are recovered in a number of sites mainly in the Tohoku District and Hokkaido, northern Japan. Owing to the recent increase in carrying out water sieving techniques in excavations, the number of the sites which yield salmon bones is increasing. In light of these discoveries, it is certain that salmon was widely captured among the Jomon populations inhabiting central and northern Japan.

Matsui (1996) pointed out that the processing method of salmon bones varied from site to site based on the observation that the preservation and composition of survived bones substantially differ from site to site. Nonetheless, it is clear that the mass of salmon bones recovered from the Jomon sites is too small to be a staple food resource. …

In the Incipient Jomon Period, caves and rock shelters were frequently used as dwelling spaces. The Kosegasawa, Fukui and Senpukuji caves, etc. mentioned above are, among others, well-known examples of the Incipient Jomon cave sites. It should be stressed, however, that nearly 90% of the Incipient Jomon sites thus far discovered are open-air sites. Also, the fact that spearheads and arrow points are usually recovered in the cave sites suggests that these sites might have been temporary encampment for hunting activities.

Assuming that the presence of a pit dwelling is an indicator of the sedentary lifeway, sedentary settlements have been present since the earlier half of the Incipient Jomon Period. A pit dwelling associated with the slender clay ridge pottery was discovered in the Hinata-nishichiku site (Yamagata) and the Maedakochi site (Tokyo). Also, pit dwellings associated with the plain pottery are found in the Sendaiuchimae and the lwashita-mukai A sites (Fukushima). Probable pit dwellings associated with the various cord-mark impressed pottery are known from the Miyabayashi site (Saitama). Most of these pit dwellings are shallow and have no interior hearths and clear postholes.

The number of pit dwellings discovered in a site is usually one or two. The sedentariness of these pit dwellers is a crucial issue. Many salmon teeth are recovered from the fill of a pit dwelling in the Maedakochi site. However, as a food salmon is not likely to have lasted longer than a couple of months or half a year. – Ryuzaburo TAKAHASHI, Takeji TOIZUMI and Yasushi KOJO, 1998

Did mobile hunter-gatherers develop ceramics and more sedentary lifestyles because of the warmer climate or because of the cold environment?

The Incipient Jomon period marks the transition between Paleolithic(旧石器時代) and Neolithic(新石器時代) ways of life, when people lived in simple surface dwellings and fed themselves through hunting and gathering. It was previously the consensus and assumed that sedentism and ceramics were developed as a result of climate warming, but this view is now being challenged because pottery is found along with pit dwellings at Maedakochi Site during this still-cold “Ice Age” climate and before the warming phase takes place.

In 2019, the study of Maedakochi, (2019, Morisaki et al.) reversed the thinking on this pointing out that sedentism and ceramics may have developed instead because of the cold environment and the exploitation of fishing resources:

“New AMS dating and environmental data suggest that intensified inland fishing in cold environments, immediately prior to the Late Glacial warm period, created conditions conducive to sedentism and the development of subsistence-related pottery.”

Support for this new viewpoint comes from an earlier study (2016, Lucquin et al,) on lipids residue analysis of pottery at the Torihama site found that pottery use in conjunction with fishing and hunting was a resilient and continuous adaptive strategy through to the Final Jomon Period:

“…the direct evidence of pottery use reported here supports the idea that pottery was invented in the late glacial period with the aim of processing a broader range of aquatic products (9) and that it retained this primary function at least until the mid-Holocene. Such functional resilience in the use of pottery in the face of altered environmental conditions, dramatic changes in the scale of manufacture, as well as proliferation in form and design, is remarkable.

The association between fishing and the hunting of aquatic mammals and pottery production may be a broader feature of preagricultural communities. Similarly high δ15N values have been found in charred deposits on Jomon pots throughout the Japanese archipelago (9, 19, 20). Lipid residue analysis has shown that marine and freshwater products were frequently processed in pottery produced by Holocene hunter–gatherers from Northeastern North America (22) and the Baltic (23, 41), and in Japan as late as the Final Jomon phase (1000 –400 B.C.) (42). Because the earliest Incipient Jomon pottery vessels were relatively small, typically 1 –2 L(43), and were only produced in low numbers, their effectiveness for substantially increasing aquatic resource production is questionable.

Our findings are more consistent with the view that pottery was initially a “prestige technology” with a limited range of uses for special foods for aggrandizing or in competitive feasting…particularly during periods of high resource abundance and social aggregation. Practically, pottery may have facilitated the rendering and storage of highly prized aquatic oils during seasonal gluts of fish that occur during short-lived episodes of spawning or migration, in concert with other larger perishable containers, as has been documented historically (44). However, it is interesting that this specialized function did not change substantially as new forms emerged and pottery became more abundant and easier to produce during the Holocene, unless the perceived “value” of aquatic foods also changed through time. A broadening of the types of aquatic resources processed in pottery in the Holocene to encompass freshwater and brackish species provides the only evidence that the tight control governing pottery use was relaxed. Increases in the size and diversity of pottery in the Early Jomon may well reflect increased ability to obtain surplus fish, to control labor, and an increased demand for fish oil for more elaborate and diverse feasting contexts.

Regardless of the significance or scale of the activity, our study shows that pottery retained its primary function despite substantial warming at the start of the Holocene, increased exploitation of the burgeoning forests, increased sedentism, and the proliferation of artifacts associated with plant processing and fishing. For this to happen, we suggest that pottery production, specifically for the exploitation of aquatic resources, must have been embedded in the social memory of these East Asian foragers for thousands of years, as a cultural norm. This dependable strategy was used by successive generations, perhaps to mitigate against risks associated with environmental change, the adaptation to new forms of subsistence, social transformation, and changes in territorial control. We hypothesize that this same functional driver was at least partly responsible for the long-distance spread of pottery westwards across Eurasia through lacustrine and riverine ecological corridors in the early Holocene….”

While Lucquin’s 2016 study established that the earliest ceramics in Japan were used initially and specifically for exploiting aquatic resources, this pattern of use was not uniformly established when compared with other early pottery sites in the Russian Far East or East Asia. Shinoda Shoda’s 2020 study found that while the Osipovka culture also used pottery to process aquatic oils at sites on the Lower Amur, a pattern of use that closely resembles the Incipient Jomon pottery use patterns studied in Japan and also on Sakhalin island up north, see Gibbs 2017), further suggesting the importance of fishing (salmonids and freshwater fish) during this period, the results from the tested Middle Amur pottery revealed lipids from animals such as sheep or goat, leading researchers to conclude that the different Amur and East Asian regions separately developed their different traditions of pottery functions, shapes as well as pottery-making techniques. And Morisaki reviewed the data and archaeological contexts (2020, Morisaki) determined that the reasons for adopting pottery are different in different geographical regions and at different times:

“Existing data indicate that there is great inter-regional variability in technology, subsistence, paleoenvironment, and adaptation associated with pottery, therefore the motivation for the adoption of pottery is distinct within various geographical, environmental, and temporal contexts in the archipelago.“

More interdisciplinary analysis, including genomic analysis of aDNA, will be necessary to establish whether there was a demic expansion of people in addition to the proposed Aquatic Neolithic cultural complex stretching from the Jomon in Japan to the Sakhalin Island to the Osipovka culture in the Russian Far Eastern Lower Amur(outlined above as per the observations by Gibbs 2017) and Shoda 2020.

As the climate warmed globally, the warm weather peaked around 6,000 years ago (middle of the early Jomon period), potteries diversified their uses from this period onwards and have been found in great abundance across the hills, along with new types of stone tools and jewelry accessories. The Okabito, as dwellers of Tama Hills are called, are consequently believed to have expanded their activities across the Hills during this period. They then developed pit traps, bows and arrows for hunting wild boar and deer, and gathered fruit and nut from the deciduous forests. They are also known to have built numerous pit dwellings in the Tama Hills at this time. Expect more posts from us on the later Jomon pit dwelling types, food subsistence strategies and ceramics next time.

References and further readings:

Morisaki, K., Oda, N., Kunikita, D., Sasaki, Y., Kuronuma, Y., Iwase, A., . . . Sato, H. (2019). Sedentism, pottery and inland fishing in Late Glacial Japan: a reassessment of the Maedakochi site, 2019 Antiquity, 93(372), 1442-1459. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.170

Ryuzaburo TAKAHASHI, Takeji TOIZUMI and Yasushi KOJO, Archaeological Studies of Japan: Current Studies of the Jomon Archaeology 高橋 龍三郎・樋泉 岳二・古城 泰. 『日本考古学』5(5), 47-72, 1998

A. Lucquin et al. Ancient lipids document continuity in the use of early hunter–gatherer pottery through 9,000 years of Japanese prehistory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 113, April 12, 2016, p. 3991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522908113.

S. Shoda et al. Late Glacial hunter-gatherer pottery in the Russian Far East: Indications of diversity in origins and use. Quaternary Science Reviews. Vol. 229, February 1, 2020, p. 106124. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106124.

Brower, Bruce, Food residues offer a taste of pottery’s diverse origins in East Asia, Science News Feb 10, 2020

Kazuki Morisaki, What motivated early pottery adoption in the Japanese Archipelago: A critical review, Quaternary International, 10 October 2020

Gibbs, K. et al., Exploring the emergence of an ‘Aquatic’ Neolithic in the Russian Far East: organic residue analysis of early hunter-gatherer pottery from Sakhalin Island Antiquity, Volume 91, Issue 360 December 2017 , pp. 1484-1500: The results of organic residue analysis of Neolithic pottery from Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East, indicate that early pottery on Sakhalin was used for the processing of aquatic species, and that its adoption formed part of a wider Neolithic transition involving the reorientation of local lifeways towards the exploitation of marine resources.